"Cultural Racism" and Colonial Caribbean Migrants in Core Zones of the Capitalist World-Economy

Nation, Racism, Coloniality

Ramón Grosfoguel

This article deals with the role of what has been called the "new racism" (Barker. 1981) in the reproduction of "imagined historical borders" that excludes colonial people from access to equal rights within the core of the capitalist world-economy. Postwar Caribbean colonial migration to the metropoles provide an important experience for the examination of racial discrimination in core zones. First, they were part of a colonial labor migration to supply cheap labor in core zones during the postwar expansion of the capitalist world-economy. Secondly, they migrated as citizens of the metropole. Thirdly, they had a long colonial/racist history with the core. Fourthly, with the contraction of the capitalist world-economy after 1973, first and second generation Caribbean colonial migrants began to be excluded from the labor market. Fifthly, they have been the target of the "new racist" discourses that attempt to keep them in a subordinated position within the core zones by using "cultural racist" discourses. Given those similarities, this article attempts to answer the following questions: Why do Puerto Ricans, Surinamese, Dutch Antilleans, French Antilleans, and West Indians experience discrimination, and in many instances, marginalization despite the fact that they share metropolitan citizenship? What are the respective differences for each metropole in the discrimination and racism experienced? How does this illustrate differences among the four core states? What is the relationship between the history of empire, the narratives of the nation, and cultural racist discourses with the socio-political incorporation of Caribbean colonial subjects in the metropoles?

The boundaries constructed by the capitalist world-system are transnationally organized along the axis of an international division of labor between core, peripheral, and semiperipheral regions (Wallerstein, 1979). This division of labor implies different forms of labor and political structures. While free-labor forms developed in the core, coerced forms of labor developed in the periphery. The capitalist world-system has historically depended on the supply of a cheap labor force in the periphery. The formation of an interstate system of sovereign states in the mid-seventeenth century became the organizational form of the modern world-system (Wallerstein, 1984). This interstate system was central to the reproduction of the hierarchical international division of labor. Core states dominated peripheral and semiperipheral states through militarism, colonial- ism, and neocolonialism. In the nineteenth century, the sovereign monarchies were transformed into nation-states. States did not represent any more the "sovereign" monarch. Instead they pretended to represent the "imagined community" known as the "nation" (Anderson, 1983).

Citizenship became an important mechanism in the formation of core-periphery borders in the capitalist world-economy. These borders constrained the extension of the privileges, resources, and rights enjoyed by the European male elites to working classes, women, and non-

European populations. Over time, citizenship rights were slowly extended to European working classes. However, these borders were always permeable. The core zones maintained a cheap labor force from the internal colonial periphery within the empire. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there were Scottish and Irish workers in London, Bretons in Paris, and African slaves in New York. Racism was a central mechanism for the maintenance of a disenfranchised labor force. It produced a colonial labor force that served as cheap labor not only in peripheral regions, but also within core zones (Wallerstein, 1979). Those colonial populations with metropolitan citizenship within the core were kept under a subordinated and second class citizenship status through the ’geoculture’ of racism in the capitalist world-economy (Wallerstein, 1991). Racism operated either to create a cheap labor force or to exclude populations from the labor market depending on the world-systemic cycles. Usually the former mechanism was used in periods of expansion while the latter in periods of contraction.

The capitalist world-system covered the whole planet by the end of the nineteenth century (Wallerstein, 1979). This expansion was entangled with other hierarchical relations. It was not only an expansion of capitalists, but simultaneously a white European male expansion which structured and reinforced the system of capitalism together with a gender, sexual, and racial hierarchy in the modern world. The racial/ethnic hierarchy at a world-scale implied a "global colonial/racial formation" of discourses and meanings about race. A global colonial/racial formation has existed since the formation of the capitalist world-system in the sixteenth century. Biological racism was the dominant discourse about race for several centuries. However, after the Second World War there was an important shift in the global colonial/racial formation. Biological racist discourses about genetically inferior "Others" fell into a crisis across continental Europe. The Nazi occupations delegitimized biological racist discourses in many continental Western European countries. The decline of biological racist discourses did not imply the end of racism in the core of the capitalist world-economy. After the defeat of the Nazi occupations in Western Europe and the 1960’s Civil Rights struggles in Great Britain and the United States, global racial discourses shifted from biological racism to cultural racism. Antiracist movements were a crucial determinant in challenging biological racist discourses. Cultural racism became part of the new geoculture of the post-1960’s capitalist world-economy. It formed part of the new global colonial/racial formation.

Postwar Caribbean colonial migrations to the metropoles provide an important experience for the examination of the outlined issues. This introduction deals with the role of what has been called the "new racism" in the reproduction of "imagined historical borders" that excludes colonial people from access to equal rights within the core of the capitalist world-economy (Barker, 198 1). This is one of the articles presented at the conference on "Les Populations Caribéennes en Europe et aux Etats-Unis" held June 20-22, 1996 at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris and sponsored by the Social Science Research Council (SSRC), the Maison des Sciences de I’Homme (MSH), and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Specifically, the conference was organized to compare the identity and cultural dimensions of migrants from non-independent Caribbean territories.

Caribbean colonial populations migrated to the Netherlands, France, Great Britain, and the United States after the Second World War. These migrations have many processes in common (Grosfoguel, 1997). First, they were part of a colonial labor migration to supply cheap labor in core zones during the postwar expansion of the capitalist world-economy. Secondly, they migrated as citizens of the metropole. Thirdly, they had a long colonial/racist history with the core. Fourthly, with the contraction of the capitalist world-economy after 1973, first and second generation Caribbean colonial migrants began to be excluded from the labor market. Fifthly, they have been the target of the new racist discourses that attempt to keep them in a subordinated position within the core zones by using cultural racist discourses. Given those similarities the questions are: Why do Puerto Ricans, Surinamese, Dutch Antilleans, French Antilleans, and West Indians experience discrimination and, in many instances, marginalization despite the fact that they share metropolitan citizenship? What are the respective differences for each country in the discrimination and racism experienced? How does this illustrate differences among the four core states?

Nation, Racism, Coloniality

In order to understand the outlined questions, three concepts are crucial: nation, race, and coloniality. These three concepts are entangled with each other. First, the concept of nation is central for the understanding of citizenship, identity, and the socio-political modes of incorporation. In order to talk about the rights (civil, political, social) and the obligations that citizenship (see T. H. Marshall, 1964) implies, we need to understand the foundational myths, invented traditions (Hobsbawn, 1990), and imagined communities (Anderson, 1983) that states, dominant elites, dominant classes, and/or dominant racial/ ethnic groups construct. A boundary/border/frontier is drawn between those who belong to and those excluded from the representations of the nation. The nation is frequently imagined in core zones as being equivalent to White middle class values and behavior (Gilroy, 1987; Rath, 1991; Essed, 1996; Balibar, 1991). The construction of national identity is entangled with racial categories.

Secondly, racism is not universal nor is it the same everywhere it exists. As Stuart Hall states, racism is always historically specific (Hall, 1980). There are two broad interpretations of racism and its shifting meanings. One is the traditional notion linked to scientific racism, that is, genetic or biological racism. The second is what is known as the new racism (Barker, 1981), sometimes called cultural racism. Taguieff (1987) and Balibar (1991) in France, and Gilroy (1987; 1993) in Great Britain use this notion to refer to a racism of ethnic absolutism or racisme differentialiste. In this kind of racism the word race is usually not even used. Cultural racism assumes that the metropolitan culture is different from ethnic minorities’ culture but understood in an absolutist, essentialist sense, that is, "we are so different that we cannot get along together," "minorities are unemployed or living under poverty because of their cultural values and behavior," or "minorities belong to a different culture that does not understand the cultural norms of our country." Nevertheless, cultural racism is always related to a notion of biological racism to the extent that the culture of groups is naturalized in terms of some notion of inferior versus superior nature.

Cultural racism is articulated in relation to poverty, labor market opportunities, and/or marginalization. The problem with the poverty or unemployment of minorities is constructed as a problem of habits or beliefs, that is, a cultural problem, implying cultural inferiority and naturalizing/fixing/essentializing culture. Culture of poverty arguments fit very well with the new cultural racist formation. Puerto Ricans in the United States and West Indians in Great Britain were among the first groups to be racialized along these lines. The classic studies arguing for a culture of poverty used Puerto Ricans as an example (Lewis, 1966). The way cultural racism is developed in each metro- pole differs according to the diverse nation formations and colonial experiences. Thus, the nation’s foundational myths are crucial in how this new racism is articulated.

There are important differences between the Anglo-Saxon world and continental European countries when discussing racial discourses. First, the United States was a colonial society with slavery as one of the most important forms of labor. Since its formation, the United States has had a large, subordinated Black population inside its territorial boundaries. Secondly, the United States and Great Britain were not invaded by the Nazis during the Second World War, unlike France and the Netherlands. This is a crucial factor which must be addressed in order to understand the differences in the construction of racial discourses after the war. Postwar France and the Netherlands developed an official discourse against biological racism, while Great Britain and the United States did not problematize biological racism until much later.

In the United States, the shift from biological racism to cultural racism emerged during the 1960’s Civil Rights struggles of African-Americans and other racialized minorities such as Native Americans, Chicanos, and Puerto Ricans. After the 1964 Civil Rights amendment to the United States Constitution, it became politically difficult continue articulating a racist discourse based on traditional, logical reductionism. In Great Britain this form of racist discourse was not problematized until the 1960’s antiracist struggles of West Indians and South Asians and the subsequent approval of laws against racial discrimination such as the 1968 Race Relations Bill. Discrimination on the basis of biological racist discourses became criminalized. As a result, racist discourses shifted and acquired new forms and meanings. Cultural racism became the dominant discourse about race in France, the Netherlands, Great Britain, and the United States. It is the central racial discourse in today’s global colonial/racial formation.

A common feature of the colonial Caribbean migrations is that each in its own way contributed to the emergence of a crisis in the metropolitan national identity, which in turn, is related to a shift in racial discourses. This is related to the third concept, the coloniality of power, which still persists despite the demise of colonialism as the main form of European/non-European relations within the capitalist world-economy. As Anibal Quijano states:

Racism and ethnicism were initially produced in the Americas and then expanded to the rest of the colonial world as the foundation of the specific power relations between Europe and the populations of the rest of the world. After five hundred years, they still are the basic components of power relations across the world. Once colonialism became extinct as a formal political system, social power is still constituted over criteria originated in colonial relations. In other words, coloniality has not ceased to be the central character of today’s social power.... With the formation of the Americas a new social category was established. This is the idea of "race".... Since then, in the intersubjective relations and in the social practices of power, there emerged, on the one hand, the idea that non- Europeans have a biological structure not only different from Europeans; but, above all, belonging to an "inferior" level or type. On the other hand, the idea that cultural differences are associated to such biological inequalities.... These ideas have configured a deep and persistent cultural formation, a matrix of ideas, images, values, attitudes, and social practices, that do not cease to be implicated in relationships among people, even when colonial political relations have been eradicated (1993, 167-69; my own translation).

Coloniality refers to the reproduction and persistence of the old colonial racial/ethnic hierarchies in a postcolonial and postimperial world. The end of colonial administrations in the modern world did not imply the end of coloniality. With the large postwar colonial migrations, the coloniality of power is reproduced inside the metropoles. No colonial Caribbean migration passed unnoticed in the European imaginary. These migrants are colonial not only due to their long colonial relationship with the metropole, but also due to their current stereotypical representation in the European imagination which is reflected in their subordinated location in the metropolitan labor market. The representations of colonial subjects as lazy, criminals, dumb, inferior, stupid, untrustworthy, uncivilized, primitive, dirty, and opportunists have a long colonial history.

Irrespective of a nation’s specific foundational myths and its particular racial constructions, the questions are the following: Given the shared citizenship, what implications did the core states’ national foundational myths have for the postwar colonial Caribbean mi- grants’ access to rights and equal treatment in the metropoles? How did these migrations undermine the foundational myths of the metropolitan nation? As Gilroy has stated regarding the English case, Black and British were incompatible notions. What role did racism play in the construction of an imagined national border? How did all of this affect the identity of Caribbean migrants in the metropoles? What strategies did Caribbean migrants develop to struggle against exclusion/discrimination or for inclusion/incorporation? How are the foundational myths re-signified over time?

United States

In the United States a central foundational myth is the "American dream." The United States is supposed to be the land of opportunity for immigrants from all over the world where the harder you work, the more successful you become. One implication of this myth is that if you fail, it is because you have not worked hard enough and that, therefore, there has to be something wrong with you. The 1787 Constitution was constructed on the basis of "We the People ..." rather than "We the citizens. . . ." Here the notion of People refers to group rights as opposed to individual rights. This implies that citizenship is perceived more in terms of group rights rather than individual rights, while excluding those outside the imagined community. This allowed for the recognition of ethnic rights for European immigrants. A country such as the United States composed of multi-ethnic immigrants did not base the reproduction of citizenship on terms of an ethno-cultural differentialist Volk-centered approach as in Germany, nor on a centralized political unity expressed in the assimilationist policies striving for cultural unity as in France (Brubaker, 1992). To be American became identified with Whiteness which was the unifying theme for all of the multi-ethnic European immigrants. The myth of the melting pot was strongly dominated by an Anglo-Saxon ethnicity and always referred to the melting of Whites. Thus, race became a central decisive category for people to be either included in, or excluded from the nation. Since the late eighteenth century, Blacks were excluded from both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The term ethnic was used to refer to Europeans and those considered to be White, while people of color were racialized and excluded from constitutional rights.

It is within the context of these foundational myths about the nation that we can discuss how citizenship defines the imagined borders, that is, who is included in, or excluded from, the imagined community. In the United States, civil rights, in terms of rights to property, and political rights, in terms of rights to vote, have always been stronger than social rights. The myth of making it through hard work, the American dream, leaves a narrow space in the social imagination for the notion of social rights. This is key to the under- standing of the United States’ underdeveloped welfare state. However, whatever the rights, they are perceived or imagined to be de- served by Whites, while racial/ethnic minorities are looked upon as intruders or opportunists who want to take advantage of these rights. In the United States the social classification of peoples has been hegemonized by White male elites throughout a long historical process of colonial/racial domination. The categories of modernity such as citizenship, democracy, and national identity have been historically constructed through two axial divisions: 1) between labor and capital, and 2) between Europeans and non-Europeans, (Quijano, I 99 1). White male elites hegemonized these axial divisions. According to the concept of coloniality of power developed by Anibal Quijano, even after political independence, when the formal juridical/military control of the state passed from the imperial power to the newly independent state, White elites continued to control the economic and political structures. This continuity of power from colonial to post-colonial times allowed the White elites to classify populations and to exclude people of color from the full exercise of citizenship in the imagined community called the nation. The civil, political, and social rights that citizenship provided to the members of the nation were selectively expanded over time to White working classes. However, internal colonial groups remained second class citizens, never having full access to the rights of citizens (Gilroy, 1987). Being American was incompatible with being Black, Puerto Rican, Indian, or Asian. Thus, the civil rights struggles of these racialized subjects were built around the notion of equality, claiming equal rights as discriminated racialized ethnic minorities within the United States. The subsequent development was the implementation of minority group rights based on affirmative action programs.

In the United States the word ethnic historically referred to cultural differences among White European groups (for example, Italian, Irish, German) while racial categories have been used to refer to people of color (for example, Blacks, Asian), erasing ethnic differences within these racially classified groups. Since the 1960’s ethnic in the United States has become a code word for race. During the 1960’s civil rights movement there was a shift in the dominant discourses on race. Rather than characterizing groups along racial lines, ethnic and migrant were coined as the new terms. This emerging dominant discourse was elaborated by Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan in their now classic 1963 study, Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italian, and Irish of New York City. The experience of people of color in the United States is equated to that of the White migrants from Europe at the turn of the century. By transmuting racial discrimination into ethnic discrimination, Puerto Ricans and African-Americans can go through the same experiences of any other ethnic group and eventually be economically incorporated as were the White European migrants before them. According to this approach, if they failed in their incorporation, it is due to some pathological condition in their culture or habits, namely, a culture of poverty. This approach obliterates the history of racial/colonial oppression experienced by African-Americans and Puerto Ricans: African-Americans’ long colonial history of slavery I political/racial barriers to upward mobility and Puerto Rico’s colonial regime that expropriated the land and incorporated the people as cheap labor in sugar plantations first and in manufacturing later in Puerto Rico and the United States. Puerto Ricans and African-Americans are not simply migrants or ethnic groups, but her colonial/racialized subjects within the United States empire.

What rights did the Puerto Rican migrants have when they arrived and how were they perceived by the metropolitan populations? This is related to the history and particularity of the type of colonialism practiced by the metropoles. The extension of citizenship to colonial Puerto Rico in 1917 by the United States institutionalized the formation of second class citizens. Puerto Ricans were supposed to have legal access to citizenship rights; however, as a racialized colonial group within the United States, their access to those rights was limited.

Unable to place Puerto Ricans in a fixed racial category (neither White nor Black) due to the mixed racial composition of the community, Euro-Americans increasingly perceived them as a racialized Other. Puerto Ricans became a new racialized subject, different from Whites and Blacks, sharing with the latter a subordinate position to the former. The film West Side Story in the early 1960’s marked a turning point where Puerto Ricans became a distinct racialized minority, no longer to be confused with Asians, Blacks, or Chicanos in the social imagination of Euro-America. This racialization was the result of a long historical process of colonial/racial subordination on the island as well as on the mainland (Vázquez, 1991; Thompson, 1995). The racism experienced by Afro-Puerto Ricans in many instances can be stronger than that experienced by lighter-skinned Puerto Ricans. However, no matter how blond or blue-eyed a person may be nor whether s/he can "pass," the moment that person identifies her/himself as Puerto Rican, s/he enters the labyrinth of racial Otherness. Puerto Ricans of all colors have become a racialized group in the imagination of Euro-Americans, marked by racist stereotypes such as laziness, criminality, stupidity, and dirtiness. Although Puerto Ricans form a multi-racial group, they have become a new race in the United States. This highlights the social rather than biological character of racial classifications. The depreciative classification of Puerto Ricans as "spics" in the symbolic field of New York designates the negative symbolic capital attached to Puerto Rican identity.

Puerto Ricans were incorporated as a cheap labor force in New York’s manufacturing industries during the 1950’s and 1960’s. The deindustrialization process of core zones after 1970 with the contraction of the capitalist world-economy massively displaced Puerto Ricans from manufacturing jobs constituting a redundant labor force in the United States’ urban areas. Puerto Ricans could not enter the top level jobs of the new service economy due to the residential segregation that racially excluded them from the best public schools that would have allowed them to upgrade their human capital. On the other hand, they were not able to enter the low-wage service jobs due to the presence of an even cheaper labor pool of new immigrants in U.S. cities. The racial construction of Puerto Ricans as lazy and criminals contributed to their current marginalization in the labor market. Moreover, the access to labor and civil rights as part of the 1960’s struggles made Puerto Ricans to be considered by employers as a more expensive labor force compared to the new immigrants. Employers today claim to prefer the "hard-working" immigrants over the "lazy" domestic minorities. Cultural racism is the new discursive form of racial exclusion in the United States. Thus, the situation of many Puerto Ricans today is not merely that of a cheap labor force. Rather the situation is one of being massively excluded from access to jobs (Grasmuck & Grosfoguel, 1997). Puerto Ricans today have a poverty rate of approximately 40%, the highest in New York City.

France

In France the national foundational myth is linked to the ideals of the 1789 French Revolution, that is, to the notion of le Droit de I’Homme, where a direct social contract is established between the state and the individual (Balibar, 1994). People are either French or non-French defined in terms of a cultural assimilationist notion which divides citizens from noncitizens. According to the official French discourse, you cannot be a Martinican French or Basque French. Thus, the category of ethnicity is not acknowledged in the French tradition. There is no official recognition of ethnic groups within the French imagined community.

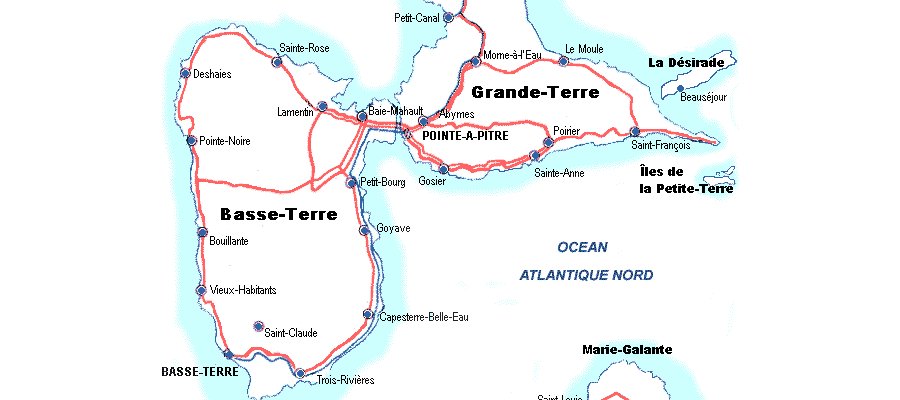

Historically, the French Antilleans have occupied an ambiguous position in the French Empire as citizens of African descent. The assimilationist drive of the French state attempted to erase this historical and cultural background through the colonialist educational, cultural, and social policies toward the French Antilles. Public schools in the Antilles date from the 1880’s and representation in the national assembly dates from 1848 (Abou, 1988; Blérald, 1988; Giraud, 1992). This is a different colonial incorporation than the French colonial policies in Africa, where public schools were established much later and representation in the national assembly is in most of the cases a post-1945 event (Marshall, 1973). Antilleans have been taught for years that their ancestors are the Gaulles.

These assimilationist policies proved to be very useful for the French colonial administration in Africa. Educated Black Frenchmen were sent from the Antilles to the African colonies as military and state officials of the French Empire (Helenon, 1997). They were a kind of middleman minority. Here middleman does not refer, as in the sociology literature, to entrepreneurs (Bonacich, 1973), but to state officials who played a similar role as the former. Rather than having only White French officials, Antilleans were sent as official representatives of the French state to Africa. They served as middle- men between the White French and the African masses in several French colonies. Instead of a White French repressing Africans, Antilleans were sent as colonial officers. They played a similar role as the middleman entrepreneurs in the British empire, that is, Antilleans served as political buffers to channel Africans’ discontent against the French officials. Fé1ix Éboué, a French Guyanese who was named governor of Chad, and Louis-Placide Blacher, a Martinican named governor of Niger, were the most dramatic examples of the middleman strategy of the French imperial state.

As an attempt to reconstitute its empire after the Second World War, the French not only incorporated the French Caribbean as French Departments but in addition named a black Guyanese man, Gaston Monnerville, President of the Conseil de la Republique. The Antilleans were used as a symbolic showcase of France’s new face for postwar colonial Africa. The subtle message was: if you assimilate to French culture as the Antilleans did, you will be granted the same rights as they are within the French empire. The Antilles served as a symbolic example of these policies.

During the postwar period, talk about race or racism was identified in the official French state discourses with the extremist Nazi positions. The word race was almost eliminated from French public discourse. Racial differences were constructed in terms of a culturalist diferentialist approach. That is, starting in the 1950’s, talk about race in France metamorphosed into talk about cultural difference, understood in an essentialist, naturalized form. This preceded, but was very similar to what happened in the United States’ post Civil Rights era.

The Algerian war was a turning point in the French colonial empire. It represented the final demise of French colonialism in Africa. However, the end of colonialism did not mean the end of coloniality. The old colonial hierarchies were now reproduced inside the metropole. North Africans were now reproduced mainly as a cheap labor force in the private labor market. They became the main source of cheap labor for manufacturing industries in cities like Paris and Marseilles. North Africans in France became a target for the new racist discourses (Taguieff, 1987). The new racism in France claimed that North Africans had cultural habits preventing them from successful incorporation into French society. Some right wing movements have gone as far as to say that North Africans are so different culturally that cohabitation is impossible, and, thus, they should be deported.

Antillean labor migration to France took off in the early 1960’s (Giraud & Marie, 1988). There was a division of labor between the colonial migrants inside the metropole. While the North Africans occupied the cheap labor positions in the private labor market, Antilleans were incorporated as the cheap labor of the French public administration. The postwar economic boom expanded the public jobs. Many jobs at the bottom of the French public administration were no longer attractive to the White French. This created a labor shortage which fostered a massive government-sponsored labor recruitment in the French Caribbean territories. Unlike many North Africans, Antilleans had French citizenship which allowed them to be incorporated into the French public service.

The French transition from imperial to postimperial policies can be conceptualized in terms of Quijano’s coloniality of power. This emphasizes the continuities rather than the discontinuities between the past and the present. Although colonialism significantly declined, coloniality was reproduced with new devices. The postwar colonial labor migration reproduced the old racial/colonial hierarchies inside metropolitan France (Balibar, 1992). North Africans were constructed as the unassimilable, undesirable, noisy, dirty, and culturally underdeveloped Other.

Antilleans once again occupied an intermediary position. They were the assimilable Other that serves as an example to the unassimilable Others. Their incorporation at the bottom of the French public administration has given them certain privileges over migrants who are incorporated mainly as cheap labor in the private labor market. This mode of incorporation into the public sphere insulates Antilleans from the fluctuations and discriminations of the private labor market. Antilleans are located in strategic and sensitive positions of the French public administration such as the immigration offices, public transportation, and hospitals. However, the Antillean situation is not ideal. They are incorporated into the public administration jobs which the White French are no longer interested in such as janitors, clerks, nurse’s aides, metro employees, and bus drivers. Qualified Antilleans are hardly ever considered for promotion to higher levels of the French public administration. French racism has created a glass ceiling through which Antilleans rarely break (Galap, 1993; Marie, 1993). This racism is articulated through a cultural meritocratic discourse. Antilleans are excluded from promotion in the public administration through a discourse about lack of qualifications, knowledge, and experience. The Antillean experience shows how citizenship is not enough to stop racist discrimination. Lack of citizenship is not what keeps North Africans and Antilleans at the bottom of the private and public labor market. Rather there is a racist exclusion of those who do not fit the dominant French representation of the imagined community.

The fact that Antilleans work with White French people in public government jobs and that they live together with Africans in public housing, gives the Antilleans an ambiguous position in the French racial/ethnic hierarchy (Marie, 1991). Some Antilleans live the illusion of sharing a position of privilege in the racial/ethnic hierarchy when working together with White French people in the better-compensated public government jobs. But, when they go home they confront the non-White others as neighbors who remind them of their own Otherness in French society. This discontinuity between those with whom they work and those with whom they live places Antilleans in an ambiguous position. Antilleans belong when it comes to receiving the benefits of public employees in France and they do not belong when it comes to job promotion within the French public administration and housing/residential location (Galap, 1993). Even their feeling of belonging should be qualified by their subordinated position within the French public administration. They are the public administration’s cheap-wage labor force. This ambiguity translates into, on the one hand, Antilleans affirming their Frenchness against the Africans on issues of identity and, on the other hand, forming alliances with Africans on issues such as police brutality in the Parisian banlieues.

It is very important to understand the strategies available to or developed by French Caribbean migrants in terms of identity. Are Caribbean migrants developing strategies of claiming rights as equal metropolitan citizens, as different national groups in a nation, or as members of the metropolitan nation?

In the metropole, first generation Antilleans discovered that the Mére-Patrie does not welcome them as French, but discriminate against them and treat them as second class citizens (Marie, 1993). Accordingly, French assimilationism is perceived as a myth. Antilleans challenged the assimilationist, non-ethnic, individual citizen ideology by developing a movement of identity affirmation during the 1980’s (Giraud & Marie, 1988). This movement was organized in associations claiming a distinct ethnic identity within the French system. Antillaise identity became a political strategy to claim rights as a distinct ethnicity within the French system, challenging the universalism of French assimilationist ideology.

The intermediary location of the first generation Antilleans in the symbolic field of the French racial/ethnic hierarchy is not necessarily shared by the second generation Antilleans in the metropole. Due to high unemployment rates and the reduction of public employees in France in the 1980’s and 1990’s during the world economic contraction, young Antilleans are no longer incorporated in the labor market as public employees as their parents were. Thus, young Antilleans are not insulated from the discrimination and harsh conditions of the private labor market. They are now more vulnerable to the racism that many Algerians, Moroccans, and Senegalese experience in the French labor market. This has important implications in terms of the emergence of new identities in the Parisian banlieues. Today second generation Antilleans often claim to be Blacks rather than Antilleans. The term Black in France, as in Britain in the early 1970’s, includes a wide range of oppressed groups. An important cultural fusion is going on today in the Parisian banlieues between Algerians, Moroccans, and Antillean youth. There is no clear idea about what will come of this cultural fusion. However, the transnational cultural fusion among these colonial groups manifests politically in the form of riots, youth festivals, and French hip-hop.

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the nation’s foundational myth is constructed around the notion of the "four pillars." This is the image of a society organized/built around four different and separate blocs/ Pillars such as the Catholics, Protestants, Liberals, and Socialists (Lijphart, 1968). The organizing principle is the division of the country between religious ideas (Protestants and Catholics), and class secular cleavages such as Liberals, middle and upper-middle classes, and Socialist working classes.

Although the four pillars have been dismantled since the 1960’s (Middendorp, 1991), the imagined community is still constructed around this myth (Rath, 1991). Accordingly, the Dutch nation is constructed as tolerant, antiracist, respectful of differences, and as the world’s mecca of liberal ideas and welfare policies (Essed, 1996). This national self-definition was questioned after the mass migration from Surinam and the Antilles to the Netherlands in the early 1970’s. First, the Netherlands promoted the independence of Surinam partly due to pressures from the Dutch population to create a juridical mechanism to stop Surinamese migration to the Nether- lands (Bovenkerk, 1975; Biervliet, 1981). The Dutch press picked up on this and developed a campaign to stop Dutch Caribbean migration. As with the British case discussed below, this created the paradoxical effect of a larger migration wave from Surinam before the border was closed. Approximately one-third of Surinam’s population migrated to the metropole in a period of six years (1973-79). Secondly, Black Dutch citizens such as Antilleans and Surinamese were represented as undesirables, lazy, dirty, criminals, not adapted to Dutch culture (Bovenkerk, 1978; Bovenkerk & Breuning-van Leeuwen, 1978; Verkuyten, 1997).

Since according to the national myth there is no Dutch racism (this is supposed to be a British problem), the talk of race was transmuted into talk about ethnic minorities who were constructed as a problem. Public policies moved from a cultural pluralist type of policies to assimilationist and neoliberal policies. Before 1980, the state promoted group specific welfare institutions with minority social workers and community building programs. They were to gradually transform the minority groups’ ways of life and adapt them to the imagined Dutch middle-class way of life (Rath, 1993: 224). Compared to the pre-1980’s policies, the post-1980 policies became less welfare-oriented and more oriented towards work and education (Lutz, 1993). In the early 1980’s, the Dutch state emphasized the construction of policies toward ethnic minorities on the assumption that this was a sociocultural problem based on their lack of adaptation to Dutch culture and manners (Lutz, 1993; Rath, 1993). Accordingly, they attempted to develop state policies of controlled integration through the cooptation of community organizations that could serve as intermediaries between the government and the community. They subsidized any organization, religious or not, that could become social partners in the policy of ethnic integration. By the late 1980’s, this policy changed once again, moving from a definition of ethnic minority policies as a sociocultural problem to that of an economic problem (Lutz, 1993; Rath, 1993). Rather than the state acting as a regulator of their socio- cultural integration, the market became the terrain where ethnics and nationals came into contact, helping ethnics adapt and assimilate to the nationals. This eliminated the emphasis on subsidizing community organizations; instead emphasis was accentuated on the magic of the market as regulator of the minorities’ sociocultural incorporation. The new economistic policies were built as part of the dismantling of the welfare state in the early 1990’s. Ethnic minorities such as the Surinamese and the Antilleans were portrayed as abusers of the generosity of the Dutch welfare state (Bovenkerk, 1978; Essed, 1996). As outsiders of the Dutch imagined community, the legitimacy of Antilleans’ and Surinamese’s access to the many welfare programs that Dutch citizens enjoyed was questioned. Thus, the neoliberal logic of the new policies was as follows: let the free market rather than the state regulate the well-being of the marginalized groups.

Cultural racism in the Netherlands operates under the ideology of minorization (Rath, 1993; Essed, 1996; Verkuyten, 1997). This term, as articulated by the Dutch scholar Jan Rath, refers to a form of discrimination, distinct from traditional biological definitions of racism that excludes and discriminates on the basis of being constructed as an ethnic minority. In the Netherlands, this construction implies that to be an ethnic means undesirable behavior and un- adaptability to Dutch norms and culture. As Rath states:

Minorisation, being an ideology of dominance, differs fundamentally from ethnicisation or ethnic categorisation, which treats ethnic as belonging per se on an equal basis, whereas in the Dutch case "ethnic belonging’ is reinterpreted as a form of non-conformity and thus undesirability.... Minorisation also differs fundamentally from racialization in the strict sense of the term. After all, minorization is not a matter of "naturalisation." Contrary to ’races," "ethnic minorities" (in the Dutch sense of the term) are not "represented as having a natural, unchanging origin and status, and therefore as being inherently different" (1993: 222; cf. Miles, 1989: 79).

According to Rath’s definition, the problem in the Netherlands is not one of racism but one of minorization. Although I agree with Rath that minorization is not equivalent to traditional biological racist discourses, this does not mean that it has nothing to do with racism. Minorization is a form of cultural racism where superiority and inferiority are constructed in terms appropriate to the Dutch middle class culture. Here cultural unadaptability lies in inferior essentialist features of the Other’s culture. The reification of culture in a hierarchy of superior and inferior cultures is a form of naturalizing differences which is entangled with biological racist discourses. The Surinamese and Antilleans have a long history of racialization and colonization in the Netherlands. They do not enter the Dutch labor market neutrally. They are racialized Others who are now referred to as ethnic minorities rather than racial minorities due to the postwar mutations in Dutch racial discourses. Racist discourses are now metamorphosed through the ideology of minorization. As Rath himself admits:

This ideology contributes to the positioning of migrant workers outside priviledged social positions. As long as "ethnic minor- ides" are defined as people that conform inadequately to the Dutch way of life, they are not considered to be fully-fledged members of the "Dutch imaginary community" and are consequently granted less access to scarce resources (1993: 222).

This exclusion is linked to race through a discourse about unfitted and abhorrent cultural behavior and norms. Dutch Caribbean migrants in the Netherlands are racialized with similar stereotypes as biological racist discourses (lazy, criminal, opportunists, parasites) but through the mediation of a culturalist discourse. These racist stereotypes serve to conceal the discrimination that Dutch Caribbean people experience in the Netherlands. This cultural racist discourse blames Dutch Caribbean cultural habits and values for the exclusion they experience in the labor market. Similar to the Puerto Ricans in the United States, Dutch Caribbean populations suffer a high marginalization in the Dutch labor market (Grosfoguel, 1997). The old racial/ethnic hierarchies of the Dutch empire are once again reproduced, but this time within the metropole. Despite the racial discursive mutations and the demise of colonialism as a political system, the coloniality of power of the present social relations shows the continuities of Dutch colonial/racial hierarchies over time.

Great Britain

In Great Britain the notion of empire, that is Britishness, defines the imagined community. To be British is equivalent to being White English. Accordingly, any talk about a Black British is an oxymoron. As Paul Gilroy said about the British case:

Nationalism and racism become so closely identified that to speak of the nation is to speak automatically in racially exclusive terms. Blackness and Englishness are constructed as incompatible, mutually exclusive identities. To speak of the British or English is to speak of white people (1993: 27-28).

West Indian migration to Great Britain provoked a crisis in the British imagined community. As in the Netherlands and the United States,’ colonial Caribbean migration played a significant role in questioning British national identity despite their relatively small numbers. The Black British claim of belonging to the imagined community was too radical for the racist construction of the British nation. Unlike European migrants, West Indians were unwelcome in Great Britain. After 1950, White workers from Poland and Ireland were accepted, but a massive flow of Black immigrants was something White British people from all social classes were unwilling to tolerate.

For the government this created a contradictory situation between the British people’s racist rejection of a massive Black colonial workers’ migration responding to labor needs in the metropoles and the postwar Labor government’s attempts to build a new imperial partners between Britain and the colonial Commonwealth governments (Dean, 1987). Many Black people from the colonies were sent to the metropole as students and trainees so that they would return and spread British ideas, favoring the West in its struggle against Communism. Negative experiences of White British racism and their hostility towards the presence of Black people would jeopardize this strategic political education, affecting British attempts to reconstitute its Colonial Empire by way of the Commonwealth. Nevertheless, the British government secretly tried to stop this colonial migratory flow (Harris, 1993; Carter et al., 1987; Layton- Henry, 1992; Rich, 1986). There were several reasons why these efforts were concealed from the public. First, immigration controls against colonial subjects would have created negative inter- national criticism that could have affected its relations with the colonial Commonwealth governments and in turn affected Great Britain’s symbolic image world-wide. After the British Nationality Act of 1948, citizenship was extended to all Commonwealth subjects. It would have been an international embarrassment to prohibit the entrance of Black British citizens while recruiting the noncitizen White European labor. Secondly, even more embarrassing and controversial would have been the association of immigration controls to racism immediately "after a world war partly waged against the racial genocide of the Hider regime" (Layton-Henry, 1992: 71). These contradictions impeded the British government from passing anti-immigration laws earlier than it did. This context allowed the massive migration from the West Indies to Great Britain during the 1950’s and early 1960’s, especially after the U.S. Congress passed a law in 1952 limiting West Indian migration.

In the mid-1950’s, there were new attempts by the conservative government to control immigration. Cyril Osborne attempted to introduce a Private Member’s Bill to control Black immigration. This is well summarized by Carter et al.:

In discussions before the Common Affairs Committee, it was pointed out that the measures proposed in the Bill were difficult to reconcile with British position as head of Common- wealth and Empire. As the Chief Whip summarized: "Why should mainly loyal and hard-working Jamaicans be discriminated against ten times that quantity of disloyal [sic] Southern Irish (some of the Sinn Feiners) come and go as they please?" The timing, too, created problems. With the forthcoming General Election, there was a desire to avoid controversial issues which might improve the chances of a Labour victory. The celebration of Jamaica’s three hundredth anniversary of British rule in 1955—at which Princess Margaret was the principal guest—also made it inopportune to present what would have appeared as ’anti-Jamaican Bill.’ This was underlined by the feeling in some quarters that colonial development and not legislation was the solution to immigration. Finally, the measure refused leave on the grounds that it was too important a measure to be left to a Private Member ... (1987: 343). )

The measure was again presented as a Draft Bill in the Cabinet by the Home Secretary in October, 1955. The same objections to Osborne’s Bill were put forward. But, in addition, new arguments were raised in the November 3 Cabinet meeting. First, they realized that there was no consent in public opinion towards this racist bill. Secondly, colonial immigration recognized as a means of increasing British labor resources (Caxter et al., 1987: 344). For the first time there were arguments in Cabinet meetings about the economic benefits of immigrants. Thirdly, there was recognition that immigration could be stopped by creating jobs in the colonies. The advantage of this alternative was that it would not jeopardize British capital and the reconstruction of the Empire in the colonial territories. As a result, the British Cabinet did not approve the bill.

Since the extension of full citizen rights to Blacks with the passing of the 1948 Nationality Act, there have been dissident voices against colonial migrants. From many circles, including British labor, there was a questioning of this legislation based on a racialized construction of Britishness. The latter excluded and included groups based on skin color. Belonging to British national identity was equivalent to being White, whereas immigrants and foreigners were associated with being Black. These racialized identities continued throughout the 1950’s.

The 1958 anti-Black riots in Nottingham and Notting Hill were the turning point that shifted British public opinion in favor of black immigration control. From then on it was a matter of time before the controls were actually approved. By July 1, 1962, the government approved an immigration control bill prohibiting the continued flow of migrants from Commonwealth territories to the Motherland. Great Britain was the only country to impose state controls over colonial Caribbean migrations to the metropole. Although migration from the Commonwealth colonies significantly declined after this date, the existence of a Black British minority was already an irreversible process.

The success and influence of African-American Civil Rights struggles in the early 1960’s stimulated and fostered Black British struggles. The 1968 Race Relations Bill was an important achievement by the anti-racist movement. However, this Bill was a turning point in the shift from biological racist discourses to cultural racist discourses. The new racism was articulated by British Conservative leader Enoch Powell in the late 1960’s. This was a racism where the word race was hardly mentioned and biological racism was criticized. To the accusation of being a racist Powell responded:

if, by being a racialist, you mean be conscious of differences between men and nations, some of which coincide with differences of race, then we’re all racialist.... But if, by a racialist, you mean a man who despises a human being because he belongs to another race, or a man who believes that one race is inherently superior to another in civilization or capability of civilisation, then the answer is emphatically no.... I do not talk about black and white. I would very much doubt if you can find a passage, you might find one, where I have used the terms black and white. I certainly have never talked about differences in quality. Never. Never. Never (as quoted in Smithies & Fiddick, 1969-.119, 122).

The new racism was articulated in terms of Blacks’ high propensity toward crime, unassimilability to British culture, and irreconcilable cultural differences. These differences were understood as natural, fixed, and essential or, as Gilroy would say, as an "ethnic absolutism." The new racist discourse is entangled with a sectarian definition of the nation. As Powell said in response to those who critiqued his views as racist, "It is even a heresy to say that the English are a white nation (as quoted in Stacey, 1970: 200). Thus, one of consequences is to stop Blacks from entering the country and if possible, repatriate them. As Powell said, ". . . suspension of immigration and encouragement of re-emigration hang together, logically and humanly, as two aspects of the same approach" (as quoted in Smithies & Fiddick, 1969: 38). Part of the new racist rhetoric is to transmute racist arguments into a rhetoric of population growth as a major factor justifying the policies against Black migration. This is how Powell articulates his justification for stopping Black migration

.... I would have thought that a glance at the world would show easily tensions leading to violence arise where there is a majority and minority . . . with sharp differences, recognizable differences, and mutual fears . . . when the numbers of minorities are small, then this danger hardly exists. It is as the numbers of the minority (which in some area is the majority) rise, that the danger grows. Consequently the whole of this issue to me ... is one of number (as quoted in Stacey, 1970: 56).

The new racism articulated by Powell was further developed by Margaret Thatcher. The association between crime and Blacks was politically mobilized during the Thatcher years to dismantle the welfare state (Hall et al., 1978). Blacks in Great Britain today experience a marginalization from the labor market similar to Dutch Caribbeans in the Netherlands and Puerto Ricans in the United States.

Conclusion

We can observe from the above examples that racism works both ways: to justify the reproduction of a cheap labor force and to exclude populations from the labor market. Historically, while incorporated in the labor market during a capitalist systemic expansion, Caribbean people have not received the same income, jobs, or status as compared to the dominant European/Euro-American populations. In times of crisis, Caribbean people have been marginalized from the labor market. In both cases, a cultural racist discourse has been mobilized to justify either a low-wage incorporation or a marginalization from the labor market in terms of cultural behavior, habits, and values that do not fit the dominant imagined community. The borders of exclusion in the new global colonial/racial formation are built on cultural racist premises rather than biological racist discourses. By essentializing and naturalizing culture, cultural racist discourses share biological racist premises. The cultural construction of the nation is a central border of racial exclusion mobilized today by metropolitan populations against Caribbean colonial migrants. The coloniality of the social relations show how the old racial/colonial hierarchies are still present within the metropoles. Colonial Caribbean migrations are a good example of how the borders of exclusion articulated by a cultural racist discourse are a global phenomenon that is not exclusive to a single core country. National identity is entangled with racist premises in all of the four core countries discussed here. Those who belong are imagined to share values with, and behave as, White middle classes. The incorporation of Caribbean colonial migrants to the core has been a traumatic experience to many White populations. Being simultaneously metropolitan citizens and colonial Others questioned the dominant representation of the nation as White. However, these same borders of exclusion created by cultural racist discourses are not mobilized exclusively against colonial Caribbean migrations. The same discourses are also mobilized today against Mexicans in the United States, Turks in Germany, Moroccans in the Netherlands, Algerians in France, Pakistanis in Great Britain, and Dominicans in Spain.

References

Abou, Antoine. L’Ecole dans la Guadeloupe Coloniale. Paris: Editions Caribéennes, 1988.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. London: Verso, 1983.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Balibar, Etienne. Masses, Classes, Ideas. New York & London: Routledge, 1994.

. Les Frontieres de la Démocratie. Paris: Editions La Découverte, 1992.

"Is There a Neo-Racism?" in Etienne Balibar & Immanuel Wallerstein. Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. London: Verso, 1991, pp. 17-28.

Balibar, Etienne & Immanuel Wallerstein. Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. London: Verso, I991.

Barker, Martin. The New Racism. London: Junction Books, 1981.

Biervliet, Wim. "Surinamers in the Netherlands," in S. Craig, ed., Contemporary Caribbeans: A Sociological Reader. Trinidad: The College Press, 1981, pp. 75-99.

Blérald, Alain-Philippe. La Question Nationale en Guadaloupe et en Martinique. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1988.

Bonacich, Edna. "A Theory of Middleman Minorities," American Sociological Review 38, 4, August, 1973, pp. 583-94.

Bovenkerk, Frank. Omdat zij anders zijn. Patronen van Radiscriminatie in Nederland. Meppel: Boom, 1978.

. "Emigratie uit Suriname." Universiteit van Amsterdam: Afdeling Culturele Antropologie, Antropologisch-Sociologisch Centrum, 1975.

Bovenkerk, Frank & Breuning-van Leeuwen, Elsbeth. "Radiscriminatie en Rasvooroodeel op Amsterdamste Arbeidsmarkt," in F. Bovenkerk, ed., Omdat zij anders zijn. Patronen van Radiscriminatie in Nederland. Meppel: Boom, 1978, pp. 17-35.

Brubaker, Rogers. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Carter, Bob, Clive Harris, & Shirley Joshi, "The 1951-55 Conservative Government Racialization of Black Immigration," Immigrant and Minorities, 6, 3, Nov., 1987, pp. 335-47.

Dean, D.W. "Coping with Colonial Immigration, the Cold War and Colonial Policy: The Labour Government and Black Communities in Great Britain 1945-5l," Immigrant and Minorities, 6, 3, Nov., 1987, pp. 305-34.

Essed, Philomena. Diversity: Gender, Color and Culture. Amherst: University of IV. Press.

Galap, Jean (1993). "Phenotypes et Discrimination de Noirs en France: Question de Méthos" Migrants-Formation No. 94, September, 1996, pp. 39-54.

Gilroy, Paul. Small Acts. London: Serpent’s Tail, 1993.

There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack’: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1987.

Giraud, Michel. L’Ecole aux Antilles. Paris: Karthala, 1992.

Giraud, Michel & Claude-Valentin Marie. "Identité Culturelle de l’immigration Antillaise," Hommes et Migrations No. 1114, 1988, pp. 90-106.

Glazer, Nathan & Daniel P. Moynihan. Beyond the Melting Pot. Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press, 1963.

Gordon, Milton M. Assimilation in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.

Grasmuck, Sherri & Ramón Grosfoguel. "Geopolitics, Economic Niches, and Gendered Social Capital Among Recent Caribbean Immigrants in New York City." Sociological Perspectives, 40, 2, Summer, 1997, pp. 339-63.

Hall, Stuart. "Race, Accumulation and Societies Structured in Dominance in UNESCO, ed., Sociological Theories: Race and Colonization. Paris: UNESCO, 1980, pp. 305-45.

Hall, Stuart et. al. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. London: Macmillan, 1978.

Harris, Clive. "Postwar Migration and the Industrial Reserve Army," in W. James & C. Harris, eds., Inside Babylon: The Caribbean Diaspora in Britain. London: Verso, 1993, pp. 7-54.

Helenon, Veronique. "Les Administrateurs Coloniaux Originaires de Guadaloupe, Martinique et Guyane dans les colonies Françaises des Afrique, 1880-1939," unpubl. Ph.D. diss., Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, 1997.

Hobsbawm, E.J. Nations and Nationalism since 1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Layton-Henry, Zig. The Politics of Immigration. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

Lewis, Oscar. La Vida: A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of PovertySan Juan and New York. New York: Random House, 1966.

Lijphart, Arendt. The Politics of Accommodation: Pluralism and Democracy in the Netherlands. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968.

Lutz, Helma. "Migrant Women, Racism and the Dutch Labour Market, in J. Wrench & Solomos eds., Racism and Migration in Western Europe. Oxford: Berg, 1993.

Marie, Claude-Valentin. "L’Europe: de l’empire aux Colonies Intérieures," in P.A. Taguieff, ed. Face au Racisme, Tome 2 Analyses, Hypothéses, Perspectives. Paris: La Découverte, 1991, pp. 296-310.

Marie, Claude-Valentin. "Par des Fréquents Transbords," Migrants-Formation, No. 94, September, 1993, pp. 39-54.

Marshall, Thomas H. Class, Citizenship and Social Development. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964.

Marshall, D. Bruce. The French Colonial Myth and Constitution-Making in the Fourth Republic. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973.

Middendorp, C.P. Ideology in Dutch Politics. The Netherlands: Van Gorcum, 1991.

Miles, Robert. Racism. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Quijano, Anibal. "Raza’, Etnia’ y Nación en Mariátegui: Cuestiones Abiertas," in Forgues, R. ed., Jose Carlos Mariátgui y Europa: el Otro Aspecto del Descubrimiento. Lima, Perú: Empresa Editora Amauta S.A., 1993, pp. 167-87.

. "Colonialidad y Modernidad/Racionalidad," Peru Indigena, 29, 1991, pp. 11-21.

Rath, John. "The Ideological Representation of Migrant Workers in Europe: A Matter of Racialization?" in Wrench, J. & J. Solomos, eds., Racism and Migration in Western Europe. Oxford: Berg, 1993, pp. 215-32.

Minorisering de Sociale Constructe van Etnische Minderheden. Amsterdam: Sua, 1991.

Rich, Paul B. Race and Empire in British Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986, Chapter 7.

Smithies, Bill & Fiddick, Peter. Enoch Powell on Immigration. London: Sphere Books, 1969.

Stacey, Tom. Immigrants and Enoch Powell. Great Britain: Richard Clay, The Chaucer Press, 1970.

Taguieff, Pierre André. La Force du Préjugé. Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 1987.

Thompson, Lanny Nuestra Isla y su Gente: La Construcción del Otro en Our Islands and Their People. Puerto Rico: Centro de Investigaciones Sociales and Departamento del Historia de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1995.

Vazquez, Blanca "Puerto Ricans and the Media: A Personal Statement," Centro 3, I, 1991, pp.5-15.

Verkutyten, Maykel "Cultural Discourses in the Netherlands: Talking about Ethnic Minorities in the Inner City," Identities, 4, I, winter, 1997, pp. 99-132.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. Geopolitics and Geoculture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

The Politics of the World Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

The Capitalist World Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

This article is a reprint from Review: Fernand Braudel Center Vol XXII: 4 1999, 409-434.

An earlier version of this article on Colonial Caribbean Migrations to the Metropoles was presented at the conference ’Les Populations Caribéennes en Europe et aux Etats-Unis," Paris, June 20-22,1996 with the support of the Social Science Research Council (SSRC), the Maison des Sciences de I’Homme (MSI-1), and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

I am grateful to Maurice Aymard, Administrator of the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, for his strong support of this project. His constant encouragement was indispensable for the success of this transnational/global academic exchange.

__

Ramón Grosfoguel is a Professor in the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.